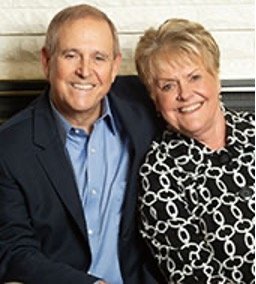

Donor Stories: Walter Anderson

Walter Anderson ’72, HD ’89 Leaves Legacy to Mercy University

To say that Walter Anderson ’72, HD ’89 rose from difficult beginnings to achieve success and happiness is a profound understatement. To escape a violent home and an alcoholic father, he dropped out of high school as a teenager and joined the U.S. Marines. After serving in Vietnam as a sergeant, and armed with a GED, he returned home ready to build a new life.

Today, Anderson is an accomplished author and playwright, a national figure in the fight against illiteracy, and a recognized motivational speaker. He is also the former editor-in-chief of Parade magazine, the co-founder of an educational services company, and a college professor. In 1994 he received the Horatio Alger award, which honors men and women who have overcome great adversity through courage, hard work, and determination. He was nominated for the honor by none other than Norman Vincent Peale, minister and author of The Power of Positive Thinking.

“The truth is, there’s not a single goal I achieved alone,” says Anderson. “Throughout my life, there have been people who have opened a door, encouraged me, or made that achievement possible. I believe that encouragement without opportunity means frustration; opportunity without encouragement means failure.”

Anderson informed Mercy President Tim Hall that he had named the University as a beneficiary in his will, joining the Universities’ Ronnenberg Legacy Society. “I feel each of us owes a debt, but not to the past—to the future,” he says. “Of course I’d like to thank every person who ever helped me; but if I really want to express my gratitude, the best way is to give others the same opportunities I was given.”

Anderson quit high school at the age of 16 to enlist. After serving almost five years in the Marines, and clutching his GED, he looked around for a suitable college program. “In those days, veterans received very little support from the government. Westchester Community College (WCC) had the least expensive tuition for the first two years, and Mercy had the least expensive tuition for a four-year school,” he says with typical candor. “I did pretty well at Westchester (he was valedictorian) and knew I should go further.”

By then, he was a full-time working journalist, married and expecting his first child with his wife Loretta. Anderson applied to Mercy for a single course, “which was all we could afford.” Then he received a call from then-Director of Admissions Andy Nelson, who asked the young man why, having done so well at WCC, he wasn’t enrolling full time at Mercy. “I explained my situation, and then, to my astonishment, Andy called the next day to inform me I had been awarded a full academic scholarship—with no strings. ‘Continue to get good grades,’ was his advice to me.” Thus Anderson, while working and attending college full time, was able to complete his studies and graduate in 1972—again as valedictorian.

When answering questions, Anderson tends to deflect attention away from his own accomplishments onto those who have helped him succeed—which is at the core of why he chose a legacy over other charitable instruments. “It’s not important that my name be remembered many years from now but that opportunities will be offered to others as a result,” he says. “The good is not seeing my name on a building. The good is what a contribution can do for students.”

In the manner of the “no-strings” scholarship he received from Mercy, Anderson has placed no restrictions on the way the College will utilize his legacy gift. “I trust the judgment of the people who make these decisions,” he says. “These are the keepers of Mercy, and they embrace Mercy’s mission. I’m quite comfortable with that. I’ve seen how Mercy approaches learning, so I’m confident that the College will continue to prepare students not only to survive our rapidly changing world but to prevail.”

This veteran publishing executive, who spent three decades at Parade Publications—as editor-in-chief, chairman, and chief executive officer—has taught as an adjunct professor of psychology and sociology at WCC and lectured at the New School for Social Research, the University of the Pacific, and Clemson University, among many others. He is also a prolific author and playwright who has written five books, including the bestsellers Meant to Be, a memoir, and The Confidence Course. His latest play, The Trial of Donna Caine, opened in fall 2018 at the George Street Playhouse in New Jersey.

Through all his years of hard work and accomplishment, Anderson has maintained a deep affection and commitment to Mercy e.

He served on the Mercy Board of Trustees from 1975 to 1988, the last eight years as chairman, and he is now a Trustee Emeritus. He established and continues to support the Ilza Williams Scholarship at Mercy in memory of Ilza Williams, an educator in the New York City Schools. Williams was a mentor and close friend of Anderson.

It’s clear that Anderson respects the values that were instilled in him as a Mercy student, beginning with that first “break” that came to him in the form of a full scholarship. “If Mercy had not given me that initial opportunity—by offering me a scholarship instead of just taking my money for that one course—I may not have finished college,” he says. “The quality education I received at Mercy is undeniable. I know that many highly regarded schools claim to be student centered, but I’ve seen Mercy do everything possible to help students succeed. Mercy really is student centered.”

Asked how one can make a difference, he replies, “No one can solve all the world’s problems, but each of us is capable of improving the world that’s within our reach. It doesn’t require significant wealth or a lofty station in life. It’s in all of us to do whatever we can with the world we can touch. That’s our measure. Besides, you feel so good when you’re helping someone else, it’s almost selfish.”